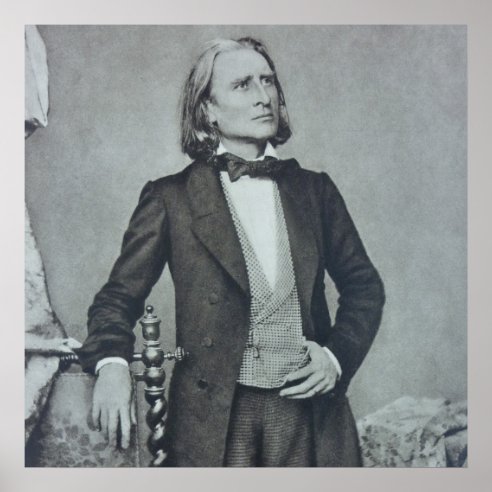

Franz liszt famous works series#

Yet by far the most notorious and celebrated period of Liszt’s career was between 18, when he gave well over 1000 concerts throughout most of western Europe, Turkey, Poland and Russia, stunning audiences wherever he went with his unique brand of pianistic devilry and showbiz razzmatazz.Ī pair of white gloves was ceremoniously removed before each performance, a second piano was situated so that amazed onlookers could admire his prowess from every conceivable angle, and he would usually submit some trifling theme by a member of the audience to a series of breathtaking improvisations. Liszt never had another piano lesson.ĭespite this early setback, Liszt remained based in Paris during the early 1830s (Chopin also settled there at this time), and became romantically involved with the Countess Marie d’Agoult (alias married popular novelist, “Daniel Stern”), who went on to have three children by him, including Cosima, who was destined to became both Hans von Bülow’s and, later, Wagner’s wife. Yet unbelievably, Luigi Cherubini, director of the Paris Conservatoire, refused him entry on the official grounds that he was a “foreign national” – in fact, Cherubini had an aversion to infant prodigies. Ignaz Moscheles, himself a front-rank virtuoso, wrote excitedly: “In its power and mastery of every difficulty, Liszt’s playing surpasses anything previously heard.” By the age of 12 he could play virtually anything at sight, and had won the enthusiastic approval of Beethoven when the young boy had played him his Archduke piano trio from memory, with the missing violin and cello parts incorporated as he went along. Liszt’s early progress was the stuff of legend. Its strings vibrated to my emotions, and its keys obeyed my every caprice.” “I confided to it all my desires, my dreams, my sorrows. “My piano is the repository of all that stirred my nature in the impassioned days of my youth,” Liszt once confessed. He devised the leitmotif technique that Wagner used to mesmerising effect in his epic operas, while many of the novel textures we now associate with the Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel were in fact invented by Liszt. He created the orchestral symphonic poem, and as one of the first great modern conductors no longer content merely to beat time, he employed a vast repertoire of subtle and passionate gestures that revealed the music’s heart and soul. Most mortals would have been more than happy to leave it at that, yet in addition to his colossal achievements as a virtuoso pianist, Liszt also composed in excess of 100 original titles for his instrument, many of which subdivide into sets of half a dozen pieces and more.

He was also a keen supporter of new music, and did much to establish the rising Nationalist schools in Russia and Bohemia, as well as encouraging the likes of Berlioz, Grieg and, most notably, Wagner. Orchestral concerts were still comparatively rare in the pre-gramophone age, so Liszt set about arranging many symphonic scores for solo piano (most famously Beethoven’s nine symphonies), in addition to composing countless sets of virtuoso fantasias on themes from operas, both popular and obscure. He virtually invented the piano recital as we know it, ensuring that the ordinary man in the street got to hear music that was normally the exclusive preserve of the educated classes. Yet he was more than a mere musical showman.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)